(Article updated 8/28/2007)

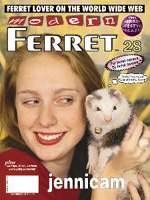

(Article updated 8/28/2007) Embedded in the Web's crumbling walk of cyber-fame there are many stars. But none glowed so brightly and for so long as Jennifer Ringley, best known as "Jenni" of the Jennicam. For seven long years she lived with a Webcam, drew worldwide adulation, but then, in December of 2003, summarily shut down her camera and disappeared from cyberspace as mysteriously as a goddess summoned back to Valhalla.

More has likely been written about Ringley and her Web cam than anyone short of Bill Gates or Tim Berners-Lee. One journalist credited her with being the "inventor of reality television" and there is more than a shred of truth in this observation. Long before the genre had been conceived as a bankable concept in the U.S., Ringley was proving its worth on the Web, and she was doing it in 1997, years before

Survivor,

Mad House, or

The Apprentice.

Feminist academics wrote that the Jennicam represented a "complex dialectic between woman as subject and woman as object, woman as both consumer and consumed." Others placed the Jennicam in the pantheon of Conceptual Art, a genre pioneered in the early 1970's by such artists as Sol Lewitt and Gilbert and George.

But

CNN best put her experiment in the language of the masses: "Ringley is the "Ed" of the Internet. She has dedicated her life to being an open book, a voluntarily Orwellian existence that allows strangers a peek of her at the height of passion, or more likely, sitting in front of her computer, staring blankly at the screen as she works at her real job, a freelance gig designing Web sites." Even

The National Review - a publication not renowned for its technology coverage or for the hyping of cyber-trends, called her "The Milton Berle of the Web," in other words, a genuine pioneer in a nascent medium whose form was molten, uncertain, and mind-boggling.

At her peak in the early 21st Century, Ringley, newly anointed

"The Darling of the Internet," reportedly attracted more than 100 million visitors a week. Incredibly, the word "Jennicam" was at one point

a more popular search term on Slashdot.org than "Linux." (When this fact became known among porn vendors, the use of the term "Jennicam" became a widespread Metatag-based scam used to lure fans of the Jennicam to hard-core porn sites. Even today, there are many such sites whose Metatags contain the word "Jennicam" - an odd but not unique case of meta-information outliving the information to which it originally (and erroneously) referred).

Within just a few years, Ringley's Jennicam had became a worldwide brand (although not a universally beloved one. As one critic noted, "the only thing really being published at jennicam.org is pictures of empty chairs, empty rooms, empty walls, or sleeping jennis"). But mention the term "Jennicam" to anyone today outside of Media Studies departments, and you are likely to receive as many blank stares as you'd get by mentioning "

Moxie" or

Burma-Shave, or

LaSalle.

What accounts for the forgetfulness of world-hyped aesthetic revolutions of just a few years past? Are we so overloaded by information that we are now suffering the social equivalent of Alzheimer's syndrome? Perhaps the spirit and temper of the world of 1997 through 2000 - the one in which the Jennicam resided - is so radically discontinuous to that of our own time, in which images of mass murder, political scandal, and nightmarish terror assault us each day, that we literally cannot recall that such a time existed. Perhaps we are ashamed of having even being alive in such an era, one typified by the kind of "cool" subjectivity shown in

this random sample from Jennicam.org's diary section:

Anyway, given that it's now after 4 in the afternoon and so far I've done nothing more than having breakfast and finishing this journal, I probably ought to try to make myself useful. Not much time to get all this work done before I head back out on my last planned travel for a while (though I'll probably be in Pennsylvania for a few days in either February or March for the filming of the movie Hollywood PA - I should find out more about that at my meeting on Monday), and the great thing about the Shout2000 trip to San Francisco is that my Ricochet should work from a lot of places around there. We're spending the last two days with our friend Courtney, since the company would only pay for two nights of hotel and we're going to be there four, and she lives in Sacramento where Ricochet may not work, but I'll still have the cam up from her home (though she has a cam site of her own as well - these things breed like bunnies!). So anyway, the laptop seems to now be functioning 100%, so I'm praying this trip goes off without a hitch. I'm off to pick up my mail and try to get some vacuuming done. Until tomorrow...Was this kind of passage an exercise in high-concept minimalism? Well, maybe. Or was it just low-concept, or maybe even no-concept exhibitionism steeped in banal self-indulgence? Well maybe that too. One could never be sure - and this ambiguity, based in the user's own clammy sense of insecurity, a direct product of cyber-voyeurship, was central to the experience of the Jennicam. Jenni knew why she was there, shimmering on your screen - Web cams really didn't seem to bother her one whit. But what were

you doing there? Who were you, anyway? A connoisseur of conceptual art? A craven, oversexed geek looking for porn? A lonely nerd looking for a friend? One could not be a party to Ringley's seven-year non-event without having the Jennicam experience reflect directly onto the dark contours of one's own soul, and in this sense, to paraphrase Nietzsche, "when you peered into the Jennicam, the Jennicam peered back into you."

Whether consciously or through sheer instinct, Jennifer Ringley showed us - through megabytes of abysmal minimalism - exactly what kind of world the West was becoming in the late 1990's, when 100 million weekly visitors routinely buzzed around a site where absolutely nothing was happening beyond a few grainy

ferrets moving around under a bed where an ordinary girl lay, asleep. A world where the details of Monica Lewinsky's slip were, in much of the popular mind, deemed more important than the names of those slaughtered in the Balkans and where millions of otherwise sensible Americans tuned into

Seinfeld or

Friends to celebrate the final victory of the ironically ersatz over the true and the real.

While Ringley publicly claims that a new

anti-nudity policy enforced by Paypal was the proximate cause of the shutdown, it is likely that the roots lay much deeper, in her own inward awareness that the world, for better or worse, had changed irrevocably. Despite the prediction of several pundits, shortly after September 11th, 2001, that "irony was dead," this new, terrifying world did not render irony, banality, or self-indulgence obsolete. It simply relocated these qualities from the private to the public spheres, projected them on real actors in a real world, crowded out playfulness, created the foundations of a real-world

Panopticon in the form of such public sector projects as the Office of Total Information Awareness, and moved on.

Today, the same Webcams that once were directed inward, at living rooms and pet cages are increasingly being

directed outward, toward parking lots, traffic intersections, and airport runways, where it seems, we hope to catch a fleeting image of an evildoer and push a button that will stop him from wreaking some senseless act of suicidal havoc. Of course, subjectivity and self-indulgence continue to thrive in the so-called Blogosphere, an area of cyberspace so completely wrapped in the

self-involved, self-referential world of innerness that it may someday grow to inhabit its own special escapist planet.

Jennifer Ringley shut down the Jennicam on New Years Day, 2004, and this event

did not go unnoticed by the major media. But nobody connected the dots between the two eras stridden by her project. Sadly, Ringley's role as the instigator of the meme that soon became so mainstreamed that it is hard to imagine a mediascape without it today is often overlooked. Fortunately, historians of Ringley's experiment have much to pore through, first, in

numerous snapshots taken by the Internet Archive, by

a moth-eaten network of unofficial fan sites that persist, a

defunct USENET group, and, of course, by the welter of news articles written about her experiment (Google the term "Jennicam" and you'll be greeted by more Jennicam-related information than you can read in an evening).

Perhaps the strangest artifact left behind by Jennicam-mania is the now defunct

Jennicam Activity Meter, an automated program that produced graphs of on-screen activity at the Jennicam. According to the Activity Meter's programmer, "It was possible to tell from this when Jennifer had got out of bed, when she'd been in the room and when she was working at the computer" without watching the Jennicam at all.

The Jennicam has been dead for almost six months now. While Ringley has apparently disappeared completely from cyberspace (an e-mail I sent her requesting information about her current status was not responded to), it is too early to say whether her self-imposed invisibility is permanent, a phase that she's now going through, or something that she's planned for a long time. If one takes into account the fact that Ringley has reserved the domain jennicam.org until January of 2009, it is likely that we have not heard the last from her and her personal Panopticon.

Postscript 06/04/05: Since writing this piece a year ago, I have received more e-mail from people asking me about the current whereabouts and disposition of Jennifer Ringley than I have about any other topic. Sorry, folks: I don't know where she is, nor has she made any efforts to contact me. But this torrent of email is sure proof that in the hearts and minds of those who experienced her in her virtual prime, Jennifer Ringley will not soon be forgotten.Update 8/28/2007: In June of 2007, information about Jennifer Ringley's current whereabouts were revealed.

Click here to read more about this development.

Labels: Cyber-Feminism, Forgotten Web Celebrities, Jennicam, Jennifer Ringley

Mirsky (and I never really learned his first name: sometimes it was Phillip, sometimes it was David, most of the time it was omitted) was one of those Ivy League-educated Kerouacian madmen who "burn, burn like fabulous roman candles" extinguishing themselves long before we even have an inkling that they exist. In Mirsky's case, bright-white fame came from the launch of his infamous "Mirsky's Worst Of The Web," in January of 1995, long before negativity became an authentic and bankable meme on the World Wide Web. But a deluge of hate mail caused him to stop producing WOTW by late 1996, passing the negativity baton to others (including this site).

Mirsky (and I never really learned his first name: sometimes it was Phillip, sometimes it was David, most of the time it was omitted) was one of those Ivy League-educated Kerouacian madmen who "burn, burn like fabulous roman candles" extinguishing themselves long before we even have an inkling that they exist. In Mirsky's case, bright-white fame came from the launch of his infamous "Mirsky's Worst Of The Web," in January of 1995, long before negativity became an authentic and bankable meme on the World Wide Web. But a deluge of hate mail caused him to stop producing WOTW by late 1996, passing the negativity baton to others (including this site).